Oceans: A Vast New Frontier for Solar Energy Harvesting

The world's oceans, covering over 70% of Earth's surface, have long been recognized as immense repositories of energy. But in recent years, they have emerged as a promising "new" source of solar energy through a technology known as Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion (OTEC).

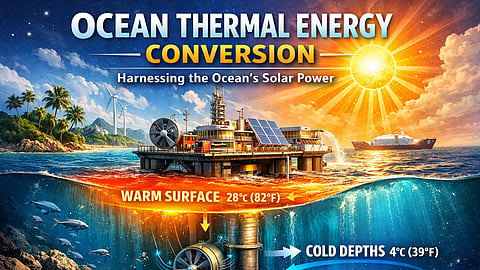

Unlike traditional solar panels that capture sunlight directly on land or rooftops, OTEC leverages the ocean's role as a natural solar collector. Every day, tropical oceans absorb staggering amounts of solar radiation—equivalent to the energy from billions of barrels of oil—creating persistent temperature gradients between warm surface waters and frigid depths.

This thermal difference, a direct byproduct of solar heating, can be harnessed to generate clean, reliable electricity and other valuable resources. As global demand for renewable energy surges amid climate change concerns, OTEC represents an innovative way to tap into this underutilized solar resource, potentially powering remote islands, producing fresh water, and even synthesizing fuels.

The Science Behind OTEC: Harnessing Solar-Infused Ocean Heat

At its core, OTEC exploits the fundamental principle that heat engines can convert temperature differences into mechanical work. In tropical regions—between about 20 degrees north and south of the equator—the sun heats surface waters to 25–30°C (77–86°F), while deep waters (typically 800–1,000 meters below) remain at a chilly 4–5°C, cooled by polar currents.

This 20–25°C gradient is sufficient to drive a power cycle, making the ocean a massive, passive solar energy storage system.

OTEC systems come in three main types, each optimized for different applications:

Closed-Cycle Systems: Warm surface water heats a low-boiling-point working fluid (like ammonia or propane) in a heat exchanger, vaporizing it to spin a turbine connected to a generator. Cold deep water then condenses the vapor back into liquid for reuse. This is the most common design for pure electricity generation.

Open-Cycle Systems: Seawater itself acts as the working fluid. Warm surface water is flash-evaporated in a low-pressure chamber, producing steam to drive the turbine. The steam is condensed with cold deep water, yielding desalinated fresh water as a byproduct—ideal for water-scarce regions.

Hybrid-Cycle Systems: These combine elements of both, maximizing electricity output while producing desalinated water. They offer flexibility for multi-use platforms, such as integrating aquaculture or air conditioning.

Large-scale OTEC could involve floating "plantships" that roam tropical waters, converting energy onsite into electricity or fuels like hydrogen (via electrolysis) or ammonia (by combining hydrogen with atmospheric nitrogen).

A single 365-MWe plantship might produce fuel equivalent to 150,000 gallons of gasoline daily, with thousands potentially meeting global transport needs.

Historical Evolution: From Concept to Demonstration

The idea of OTEC dates back to 1881, when French physicist Jacques d'Arsonval proposed using ocean temperature differences for power. The first operational plant was built in Cuba in 1930, but it was small and short-lived.

Serious development ramped up in the 1970s amid oil crises, with the U.S. Department of Energy investing $260 million from 1975–1982. Key milestones included the 1979 Mini-OTEC test in Hawaii, which generated 50 kW gross power, and the 1980 OTEC-1 demonstration, validating components at 1-MWe scale.

Funding cuts in the 1980s stalled progress due to falling oil prices, but Hawaii's Natural Energy Laboratory of Hawaii Authority (NELHA) kept the flame alive, operating a 250-kW plant in the 1990s and a 105-kW Navy-supported facility since 2015. Globally, interest has revived with climate goals, leading to pilots in Japan, the Pacific Islands, and beyond.

Advantages: A Multifaceted Renewable Powerhouse

OTEC's appeal lies in its reliability and versatility. Unlike intermittent solar or wind, it provides baseload power—operating 24/7 with minimal downtime—thanks to the ocean's stable thermal gradients. It produces no direct emissions, reducing reliance on fossil fuels and cutting air pollution.

Byproducts like desalinated water (up to millions of gallons daily from large plants) address water scarcity, while nutrient-rich discharge water can boost aquaculture, enhancing marine productivity similar to natural upwellings.

Economically, OTEC avoids land-use conflicts, making it ideal for islands like Hawaii, Guam, or small Pacific nations dependent on imported fuel. It can also generate fuels like ammonia, which has a high octane rating and low emissions, potentially powering vehicles with minor engine tweaks.

Multi-use platforms integrate seawater air conditioning (SWAC), farming, and desalination, amplifying benefits.

Environmentally, widespread adoption could displace fossil fuels, curbing CO2 emissions. Studies suggest minimal impacts if scaled thoughtfully, with potential to enhance ocean ecosystems.

Challenges and Limitations: Hurdles to Overcome

Despite its promise, OTEC faces significant barriers. High upfront costs—for massive cold-water pipes (up to 1 km long) and platforms—make it capital-intensive, with estimates for delivered fuel at $0.30–$0.60 per gallon (in 1990s dollars), competitive only with subsidies.

Technical challenges include biofouling (marine growth on pipes), corrosion, and storm resistance for floating systems.

Environmental concerns arise from pumping vast water volumes: a 100-MWe plant might process 500,000 cubic meters per hour, potentially affecting plankton or creating plumes that alter local currents if densely deployed. Logistics for fuel transport and infrastructure adaptation (e.g., ammonia engines) add complexity.

Current Projects and Future Prospects

As of 2026, OTEC is transitioning from pilots to commercial scale. Hawaii hosts operational demos, including a 105-kW plant supplying grid power. In 2025, Japan upgraded its Okinawa plant to 1 MW, and Hawaii launched a floating pilot. Global OTEC aims for the first commercial-scale generator in the Pacific, potentially online by now.

Market projections are optimistic: The OTEC plant sector could grow from $0.2 billion in 2024 to $1.1 billion by 2034, driven by companies like Lockheed Martin and startups in multi-use systems. Research focuses on efficiency boosts, like solar-OTEC hybrids, and environmental assessments.

With supportive policies, OTEC could supply gigawatts by mid-century, especially for equatorial nations.

Conclusion: Unlocking the Ocean's Solar Potential

Oceans are not just vast bodies of water—they are dynamic solar energy reservoirs waiting to be tapped. Through OTEC, we can harness this "new" source to provide sustainable power, water, and fuels, addressing energy security and climate challenges.

While hurdles remain, recent advancements signal a bright future. As technology matures, OTEC could redefine renewable energy, turning the blue planet's seas into a cornerstone of our green transition.