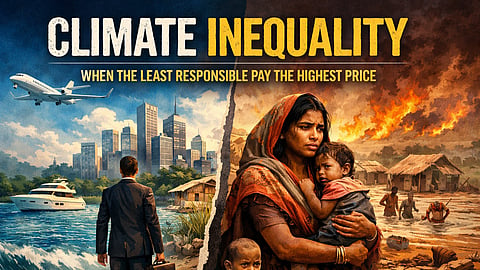

Climate Inequality: When the Least Responsible Pay the Highest Price

Climate change is often described as a global crisis, but its impacts are anything but equal. While greenhouse gas emissions originate largely from industrialised nations and wealthy populations, the harshest consequences—floods, droughts, heatwaves, food insecurity, and displacement—are disproportionately borne by the world’s poorest and most vulnerable communities.

This stark imbalance is known as climate inequality, a defining moral and political challenge of the 21st century.

At its core, climate inequality exposes a deep injustice: those who have contributed least to the climate crisis are paying the highest price, while those most responsible often possess the greatest capacity to adapt and recover.

The Unequal Carbon Footprint

A small fraction of the global population accounts for a majority of emissions. High-income countries, which industrialised early and continue to consume disproportionately, are responsible for the bulk of historical greenhouse gas emissions. In contrast, low-income nations—many of them in Africa, South Asia, and small island states—have minimal carbon footprints yet face escalating climate risks.

Even within countries, inequality is evident. Wealthier households emit far more due to higher consumption of energy, travel, and goods, while poorer communities often live in climate-vulnerable areas with limited access to cooling, insurance, or resilient infrastructure.

Frontline Communities and Climate Vulnerability

Climate impacts tend to strike hardest where resilience is weakest. Coastal villages, informal urban settlements, indigenous territories, and arid rural regions are increasingly exposed to rising seas, extreme weather, and ecosystem collapse. For many of these communities, climate change is not a future threat—it is a daily reality.

Farmers dependent on rainfall face crop failures; fisherfolk confront depleted oceans; urban poor endure deadly heat without adequate shelter or water. Climate shocks often push vulnerable families deeper into poverty, eroding livelihoods, health, and education, and trapping generations in cycles of deprivation.

Climate Change and the Global South

Developing nations face a dual burden: managing climate impacts while striving for economic development. Extreme weather events can wipe out years of development gains in a single season. Infrastructure damage, food shortages, and health crises strain already limited public finances.

Ironically, many of these countries are being urged to transition rapidly to low-carbon pathways without receiving sufficient financial or technological support. This imbalance raises fundamental questions about fairness, responsibility, and global solidarity.

Gender, Health, and Social Dimensions of Inequality

Climate inequality is not only geographic—it is deeply social. Women and girls often bear a disproportionate burden due to their roles in food production, water collection, and caregiving. Climate-induced resource scarcity increases risks of malnutrition, school dropouts, and gender-based violence.

Health impacts are also unequal. Heat stress, air pollution, and climate-sensitive diseases affect low-income populations more severely, particularly where healthcare access is limited. Children, the elderly, and people with disabilities are among the most at risk.

Loss, Damage, and the Question of Accountability

As climate impacts intensify, the conversation has shifted beyond mitigation and adaptation to loss and damage—the irreversible harms caused by climate change. These include lost lives, submerged land, cultural heritage erosion, and forced displacement.

Vulnerable countries have long called for financial mechanisms to address loss and damage, arguing that climate justice requires accountability from major emitters. While international recognition of this issue has grown, funding remains inadequate and slow, underscoring the gap between promises and action.

Bridging the Divide: From Climate Action to Climate Justice

Addressing climate inequality requires more than cutting emissions; it demands a justice-centred approach. This includes fair climate finance, accessible technology transfer, and inclusive decision-making that amplifies the voices of those most affected.

Adaptation investments must prioritise vulnerable communities, while development pathways should be designed to be both low-carbon and poverty-reducing. Equally important is empowering local solutions—indigenous knowledge, community-led resilience, and equitable urban planning.

Conclusion: A Defining Test of Our Time

Climate inequality is a mirror reflecting the broader inequities of our world. How humanity responds will define not only the success of climate action, but also the moral character of the global community.

A warming planet does not have to mean a more divided one. With political will, shared responsibility, and a commitment to justice, climate action can become a force for greater equity—protecting both the planet and the people who depend on it most.