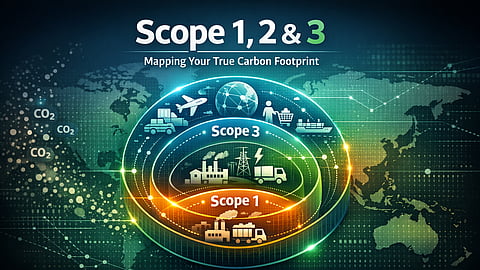

Decoding Corporate Carbon Footprints: The Essential Guide to Scope 1, 2, and 3 Emissions

In an era where climate change dominates global headlines, businesses and organizations are under increasing pressure to measure, report, and reduce their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The concept of emission scopes—divided into Scope 1, 2, and 3—provides a standardized framework for this, originating from the Greenhouse Gas Protocol, the world's most widely used GHG accounting standard.

This article delves into each scope, offering clear explanations, practical remedies, and key insights to help stakeholders understand their carbon impact and take meaningful action. Whether you're a corporate leader, environmental advocate, or curious individual, grasping these scopes is crucial for driving sustainable change.

Understanding Scope 1 Emissions: The Direct Contributors

Scope 1 emissions are the most straightforward category, encompassing all direct GHG emissions from sources that are owned or controlled by an organization. These are essentially the "in-house" pollutants released right at the point of activity, making them easier to track and manage compared to indirect sources.

Explanation and Examples

At their core, Scope 1 emissions arise from combustion processes and chemical reactions within an entity's operations. Common examples include:

Fuel burned in company-owned vehicles or fleets, such as diesel in trucks or gasoline in cars.

On-site energy production, like natural gas boilers for heating or manufacturing.

Fugitive emissions from leaks in refrigeration systems (e.g., hydrofluorocarbons or HFCs) or industrial processes (e.g., methane from oil and gas operations).

Agricultural activities, such as enteric fermentation in livestock or manure management on farms.

These emissions are typically measured in carbon dioxide equivalents (CO2e) to account for the varying global warming potentials of gases like CO2, methane (CH4), and nitrous oxide (N2O). For instance, a manufacturing plant might report Scope 1 emissions from its furnaces, directly tying back to its fuel consumption data.

Remedies and Reduction Strategies

Reducing Scope 1 emissions often involves operational upgrades and behavioral changes. Key remedies include:

Electrification and Efficiency Improvements: Switching from fossil fuel-based equipment to electric alternatives, such as electric vehicles (EVs) or heat pumps. For example, installing energy-efficient boilers can cut emissions by up to 30%.

Fuel Switching: Transitioning to low-carbon fuels like biofuels or renewable natural gas (RNG) for processes that can't be electrified easily.

Leak Detection and Maintenance: Implementing regular monitoring with technologies like infrared cameras to prevent fugitive emissions, potentially reducing leaks by 50-70% in industries like oil and gas.

Process Optimization: Adopting cleaner production methods, such as carbon capture and storage (CCS) for unavoidable emissions, which can capture up to 90% of CO2 from industrial sources.

Insights: Scope 1 often represents a smaller portion of total emissions (typically 10-20% for most companies), but it's where organizations have the most control. Early action here can yield quick wins, boosting investor confidence and regulatory compliance, especially with policies like the EU's Emissions Trading System (ETS).

Demystifying Scope 2 Emissions: The Energy Indirects

Scope 2 emissions shift the focus to indirect emissions stemming from the consumption of purchased energy. While not emitted directly by the organization, they are a consequence of its energy demands, making them a critical link in the emissions chain.

Explanation and Examples

These emissions occur at the site where the energy is generated, but they are attributed to the end-user. The primary culprit is electricity purchased from the grid, but it also includes steam, heating, and cooling bought from third parties. Examples abound:

Electricity used for lighting, machinery, and data centers in offices or factories.

District heating systems in urban buildings.

Purchased steam for industrial processes in sectors like food processing.

Calculation relies on emission factors from energy providers, which vary by region—coal-heavy grids like those in parts of Asia have higher factors than renewable-dominant ones in Scandinavia. A tech company, for instance, might calculate Scope 2 based on its server farm's power usage, even if the actual emissions happen at a distant coal plant.

Remedies and Reduction Strategies

Scope 2 reductions emphasize smarter energy procurement and efficiency. Effective approaches include:

Renewable Energy Procurement: Signing power purchase agreements (PPAs) for wind or solar energy, or buying renewable energy certificates (RECs) to offset grid emissions. Companies like Google have achieved 100% renewable matching through such strategies.

Energy Efficiency Upgrades: Installing LED lighting, smart thermostats, and efficient HVAC systems to lower overall consumption, often reducing emissions by 20-40%.

On-Site Renewables: Generating power via rooftop solar panels or small wind turbines, which directly displaces purchased energy.

Supplier Engagement: Pressuring utilities for greener grids through advocacy or collaborative initiatives.

Insights: With the global push toward decarbonized electricity (e.g., via the Paris Agreement), Scope 2 is becoming easier to address. However, location-based vs. market-based accounting debates highlight challenges—market-based methods allow credits for renewables, but they can sometimes overstate reductions if not verified properly.

Tackling Scope 3 Emissions: The Vast Value Chain

Scope 3 is the broadest and most complex category, covering all other indirect emissions not included in Scopes 1 or 2. These occur upstream and downstream in an organization's value chain, often dwarfing the others in scale.

Explanation and Examples

Divided into 15 categories by the GHG Protocol, Scope 3 captures emissions from suppliers, product use, and end-of-life disposal. Key examples:

Upstream: Purchased goods and services (e.g., raw materials like steel or electronics), employee commuting, and business travel.

Downstream: Use of sold products (e.g., fuel burned in vehicles sold by an automaker) and waste disposal.

Other: Investments, franchises, and leased assets.

For a consumer goods company, Scope 3 might include emissions from farming ingredients, shipping products, and consumers using appliances. These can account for 70-90% of total emissions in sectors like retail or apparel, making them a blind spot if ignored.

Remedies and Reduction Strategies

Addressing Scope 3 requires collaboration beyond organizational boundaries. Proven remedies:

Supply Chain Optimization: Auditing suppliers and favoring low-carbon ones, or using tools like life-cycle assessments (LCAs) to redesign products. For example, switching to sustainable sourcing can cut emissions by 15-25%.

Product Design for Circularity: Creating durable, recyclable goods to minimize end-of-life impacts, such as through circular economy models.

Employee and Customer Engagement: Promoting remote work, carpooling, or incentives for low-emission product use (e.g., energy-efficient appliances).

Partnerships and Innovation: Collaborating on initiatives like the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi) to set chain-wide goals, or investing in carbon offsets for hard-to-abate areas.

Insights: Scope 3's complexity arises from data gaps and shared responsibility—emissions might be counted in multiple entities' reports. Yet, it's where the biggest opportunities lie; companies like Unilever have reduced Scope 3 by embedding sustainability in supplier contracts, influencing entire industries.

Emerging regulations, such as the EU's Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), are mandating Scope 3 disclosure, pushing transparency.

Key Insights: Challenges, Opportunities, and the Bigger Picture

Across all scopes, common challenges include data accuracy, double-counting risks, and evolving standards. However, insights reveal that integrated reporting (e.g., via tools like CDP or GRI) can uncover cost savings—energy efficiency often pays for itself in 1-3 years.

In high-emission sectors like aviation or cement, breakthroughs in green hydrogen and CCS offer hope. Moreover, investor scrutiny (e.g., from ESG funds) rewards proactive firms, while laggards face reputational and financial risks. A holistic approach—combining technology, policy advocacy, and cultural shifts—is essential for net-zero ambitions.

In conclusion, mastering Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions is not just a compliance exercise but a roadmap to resilience in a low-carbon future. By understanding these categories, implementing targeted remedies, and leveraging insights from global best practices, organizations can significantly curb their environmental footprint.

As we approach critical tipping points in climate science, the time for action is now—let's commit to measuring what matters and building a sustainable legacy for generations to come.